By ALYA AHMAD, MD

Call it white privilege or health disparity, it appears to be two sides of the same coin. We used to consider ethnic or genetic variants as risk factors and prognostic to health conditions. Yet what has become more relevant is the Social Determinants of Health (SDH) as causal to disease prevalence and complexity to health care.

This is was made more evident, in one of the many examples of care I encounter daily as a pediatric hospitalist in the San Joaquin Valley region. A 12-year-old Hispanic boy is admitted with a ruptured appendix and develops a complicated abscess with an extensive hospitalization due to his complication. Why? Did he have the genetic propensity for this adverse outcome? Was it because he was non-compliant with his antibiotic regimen? No.

Rather it is the social construct and circumstance that hurdles his care. First, he had trouble getting to a hospital or clinic. Both his parents are migrant workers with erratic long hours. Despite intense pain, he did not want to burden his family and further delays evaluation. In silent desperation, his mother is bounced around from clinic to emergency room and back to their rural based clinic then referred back to the same emergency room more than 20 miles from their home. By the time he is admitted 2 days later, he is profoundly ill. The surgeon is called in the middle of night for his emergent open surgical appendectomy and drainage. Even after his post-operative care while on broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, his conditions persists with fevers, chills, and pain. Yet, he continues to deny his symptoms to avoid worrying his mother. His Spanish speaking mother never asserts or doubts why even despite surgery and drainage he was not healing per the usual expectation. Five days post-operative he requires another procedure for complex abscess drainage. What are the true determinants to his complicated outcome?

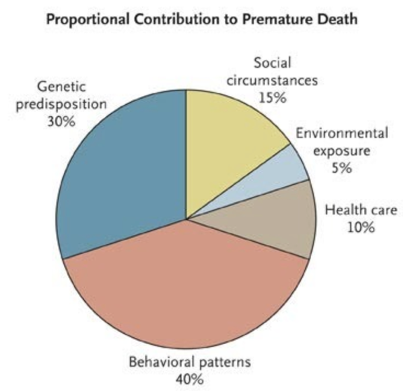

In a 2007 study, “We Can Do Better-Improving the Health of the American People, The New England Journal of Medicine, the proportional contributors to premature death are described, and behavioral and social patterns dominate:

More recently there appears to be a paradigm shift in how health care systems and access is viewed. Health care delivery plays a relatively minor role in its impact to premature death. What governs individual behavior of the patient is a result of SDH, which are a product of:

- Barriers to appropriate health care

- Economic instability

- Unsafe environment

- Poor health literacy and education

- Limited social and community support

- Food scarcity

- Social discrimination and language barriers

These are just a few of the factors that part represent and challenge patient care and health inequities. Genetics is relatively a minimal risk factor to disease condition. We cannot just say that Blacks have a greater risk of heart disease, diabetes, hypertension etc. We need to ascertain the social context of our diverse populations in order to address incidence of chronic disease and its effects. It cannot be just genetics of the immigrant, the refugee, the homeless, or impoverished population that lead to the greater morbidity and mortality.

As a pediatrician practicing in the central valley, I see the consequence of social complexity in pediatric care delivery, daily. In a recent 2017 report by Center for Regional Change and Pan Valley Institute, California San Joaquin Valley, children are “living under stress”. They are not only born under duress but face lifelong barricades to better health, physical and mental. The occurrence of child poverty level in counties of the SJV are profound. The graph exhibits poverty levels of 28 to 38 % in the valley:

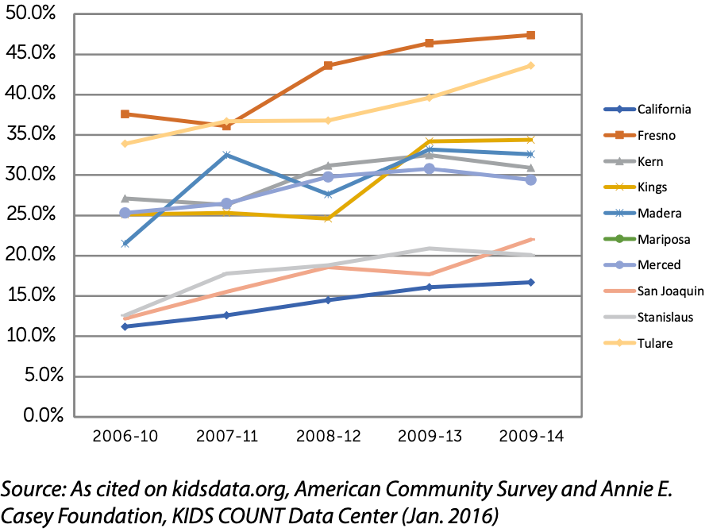

Even more, California has a large (Gross Domestic Product) in terms of agriculture production in the country. When you break it down by county, crop value in the valley ranks high. Yet, the valley with the largest crop production also paradoxically has the highest child poverty in the state. Even with economic stability, poverty remains rampant in the central valley. The rates of concentrated poverty, where more than 30% of population are below the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), are greatest in SJV areas and are increasing over time:

Percentage of children under 18 living in areas of concentrated poverty

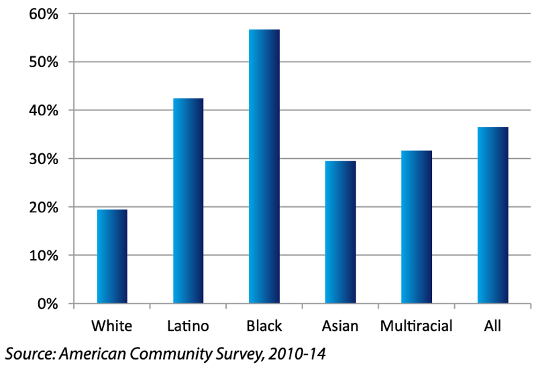

Furthermore, poverty rates are highest among children of color. The ethnic gap in poverty is 10 to 35%.

Percentage of San Joaquin Valley children under 6 in poverty, by race/ethnicity

Despite economic potential, health care access and resources also operate at crisis levels. Rural communities with geographic obstacles face shortages in provider availability and health care systems. The same fertile communities of SJV producing the food source of the nation, ironically have the larger limitations of access to food. Food scarcity, where food and especially healthy food is either limited or uncertain, remain above 26 to 29% when compared to food shortage for whole of California at 23%.

Estimated percentage of children under 18 living in households with limited or uncertain access to adequate food, 2014

The overall pollution burden, which represents the potential exposures to pollutants and adverse environmental conditions caused by pollutants, is the greater than 8 to 10% in the Valley. Not surprisingly, asthma and lung diseases in SJV districts are highest in central California.

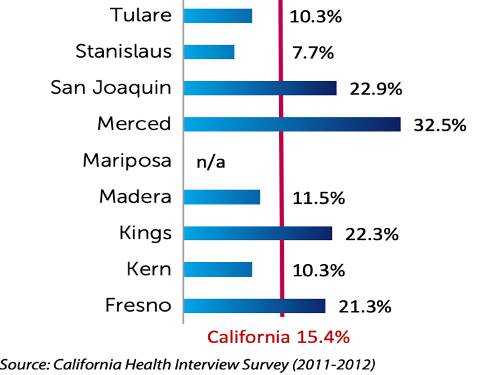

Percentage of children diagnosed with asthma

Scientific literature now highlights Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) in which the number of exposures of toxic stress and trauma: child abuse, neglect, domestic violence, parental drug/ alcohol exposure, incarceration, separation, and or stress, is scored. The greater number of ACE’s, the greater degree of maladaptive physiological, neuro-architectural, immunological, and epigenetic effects on the fetal and developing children. The effect of ACE’s on mental health and chronic medical conditions, (asthma, diabetes, Cancer, heart disease, obesity, etc.) correlates exponentially with the number of ACE exposures. Such that, if a child has more than 4 ACE exposures the risk of developing COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary disease) as an adult increase by 260%; for depression it increases by 460%. In California the prevalence of the number of ACE with 2 or more toxic level stress exposures early in the child’s life is at 16.7%. Per kidsdata.org, a Population Reference Bureau, analysis of data from the National Survey of Children’s Health and the American Community Survey (Mar. 2018) the incidence of parent reported of ACE scores >2 for the SJV counties is even higher: Fresno, Tulare, Madera, and Merced cities range from 17.9 to 19.3% of the population. Such that 1 out of 5 children are exposed to toxic level stress. The consequences of that same child becoming an adult with a chronic medical and or mental condition cannot be discounted.

Health vulnerabilities in the valley are extreme and burden the limited health care systems servicing the community in SJV. The current California governor’s administration has acknowledged this fact. Support to implement and maintain medical education and training programs with retention of providers in SJV is necessary. Specific funding allotments for improving mental health, air quality, homelessness among many other SDH’s in the region is vital.

Dr Nadine Burke-Harris, California first female Surgeon General, who recently visited the Valley, announced an ACEs Aware campaign. The ACEs Aware initiative is a first-in-the-nation statewide effort to screen for childhood trauma and treat the impacts of toxic stress. The bold goal of this state-wide initiative is to reduce Adverse Childhood Experiences and toxic stress by half in a single generation, and to launch a national movement to ensure everyone is ACEs Aware. ACE’s Aware is not only a complete program with training and readily available tools to implement screening, it is fully reimbursed in preventative pediatric care setting.

Starting early, as pediatricians we can Identify kids exposed to ACEs through routine screenings and establish prevention programs in healthcare, schools and youth-serving organizations. In their critical and early developmental stages, resources allocation of health services can be provided. It is also imperative to know and stay engaged with our region’s leaders, telling our stories in health care, enlist our community partners, schools, regulatory agencies, and empower our patients and families to advocate for social and health equity.

Alya Ahmad MD FAAP is a pediatric hospitalist who has worked in both private and academic centers as a professor and faculty and blogs at The Context of Care.

The post The Social Context and Vulnerabilities that Challenge Health Care in the San Joaquin Valley of California appeared first on The Health Care Blog.